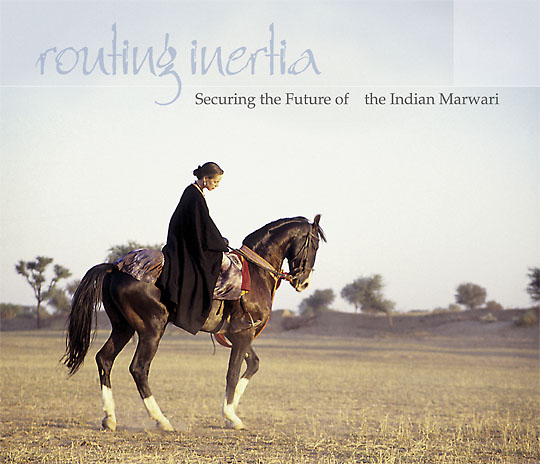

Routing Inertia – February 2007

kip mistral

The day her destiny quietly set her down at a rural horse fair in Nagaur, India, Francesca Kelly was vacationing in Rajasthan, on an equestrian tour with her husband James.

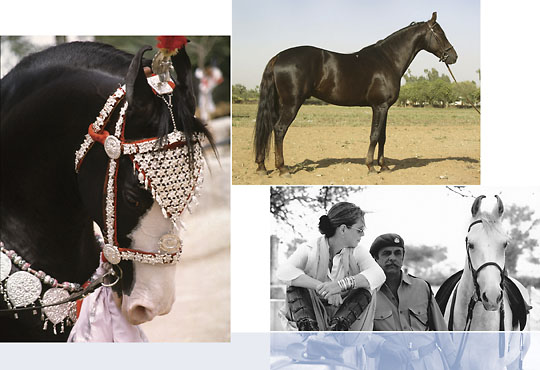

She wandered casually through lines of tethered horses for sale, marveling at the beauty of the elegant Marwari horses whose exotic ears curve inward to touch their tips. When a mare shackled in iron hobbles raised her head, met Francesca’s eyes and called to her imperiously, Francesca naturally approached and caressed her to offer comfort. The mare simply would not let her go, neighing as the stranger turned to leave, willing her to take her from this place. This was Francesca’s introduction to the forceful, vibrant personality of the Marwari horse. Mesmerized by the mare’s insistence and feeling her life was about to change, Francesca seemed to have no choice. She bought the mare and named her Shanti.

Francesca, born in Washington D.C., to British parents, looks back at that moment twelve years ago as an epiphany. It was the beginning of a series of encounters that pushed her onto a path less traveled, for surrendering to Shanti’s summons was only part of the alchemical transformation of Francesca that began as she toured Rajasthan.

Riding the open spaces in the warm Indian sun and camping under the stars at night, had revived her childhood love of the desert culture in Egypt, where her stepfather, Sir Harold Beeley, had served as British Ambassador for seven years. She remembered those earlier hot-blooded desert horses and savored an exhilarating sense of freedom as she rode Rajput land on the fiery, exciting Marwari, who seemed almost a symbol of the freedom she herself craved.

Francesca writes poignantly about this sense of expansion in her magnificent photographic book Marwari: Legend of the Indian Horse…“To know and love the Marwari is to re-enter the magical realm of our childhood, a world of castles and heroes, intrigues and passion, dark deeds and mythical horses. A time when women dressed as queens, and queens rode like warriors, a time when men fought to live and lived to fight on the battlefields and never went gently into that good night. It is a golden opportunity to embrace the twilight world of the desert, the creative frenzy of a thousand and one festivals, and to partake in the daily rituals that help reawaken our perceptual innocence and calm our unruly souls.”

But despite Francesca’s delight in bringing Shanti into the protection of the camp, the tour leader had to explain to the Kellys the reality surrounding the export of Marwari horses from India. Kanwar Raghuvendra Singh (“Bonnie”), heir to his ancestral estate Dundlod Fort (built 1750) and operator of the largest Marwari stable in India, knew the problems only too well. Francesca found a mixed array of challenges awaiting her, tangling history with politics.

In the northwest of India, the soul of Rajasthan [“The Land of Kings”] was infused with the ethos of a thousand-year-old culture that gloried in honor and battle. In these feudal times a social caste system had been developed for horses as well as for humans. The valiant Marwari horse was bred especially for fighting and was assigned to its own caste. Within these systems, only a Rajput warrior could ride a Rajput war horse. Sadly, over centuries of warfare, unimaginable legions of brave warriors and equally courageous horses expired in battles of such magnitude that tens of thousands of horses and men fought and were lost in each.

When the British Empire succeeded in taking rule of Rajasthan after 1917, where incessant warring and even infighting had prevented a united, effective resistance, there was no place for this horse, the former spiritual figurehead of the now defeated Rajput state. In 1947, India won independence from the British. But nine years later the nation’s socialist government methodically destroyed what spirit might remain of the Rajput warrior by stripping the former rights of pan-Indian rulers, and emptying royal and aristocratic stables of the horse that had carried the Rajput through history. Thousands of purebred Marwari were thrown to the winds—stallions castrated, disposed of to peasants as beasts of burden, fine mares were put to any Indian stud to beget yet another beast of burden, untold Marwari shot just to get them out of the way. A few pure Marwari fell into the hands of villagers who, in their ignorance of handling horses, tethered them by one foot in a tiny byre, where their care fell to the women and children. The fortunate ones were kept near the kitchen to prevent theft. The proud Marwari warhorse archetype faded into obscurity.

But when political tension had eased, backyard Marwari breeders began to exchange ideas. Certain royal families supported the preservation of the Marwari and its important bloodlines, but there was not a concerted, organized effort to revitalize the pure breed, not even a studbook. Gradually, however, equestrian tourism in Rajasthan that utilized the Marwari—such as the tour the Kellys were on—exposed outside parties to the value of this unique horse.

In that year, 1995, the Marwari horse was not supported in any effective way by the government. Yet ironically the breed was on a list of threatened breeds that could not be exported from India, since several years earlier the government had declared the breed as one of the indigenous livestock, and was considered to be part of the country’s national wealth. At the time it was estimated that only 500-600 Marwari horses in the country were considered to be untainted by crossbreeding.

Yet despite the impediments, Francesca’s desire to take Shanti home to the U.S. was indomitable. As she learned more about the heritage and nature of the Marwari, she felt called to work not just on behalf of her own horse, but for the entire undermined breed. Her vision that developed was to help reclaim the indigenous integrity of the proud and ancient Marwari horse in India, it’s own land, at the same time promoting the introduction of the horse outside the country.

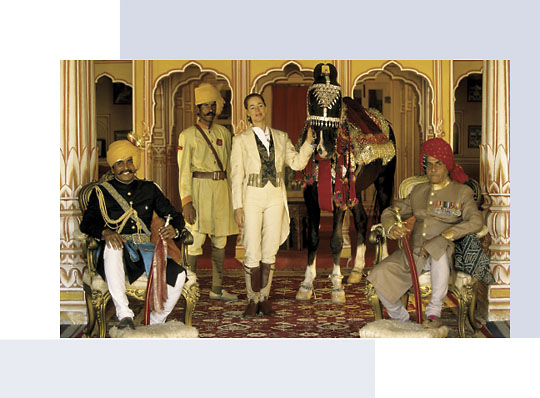

She bought several more of the finest horses in Rajasthan, and with Bonnie assisting in negotiations, began to work her way through the layers of governmental red tape, and even problems with U.S. officials. But faced with the prospect of challenging an entrenched establishment view, the daughter of diplomats was not in the least intimidated by the need to develop her own mixture of diplomacy and defiance. Francesca found herself relating to a certain class of women adventurers peculiar to the British that break the traces of convention to follow their cause. She could somehow battle through obstacles with an almost cavalier élan.

Francesca traveled frequently back and forth between Martha’s Vineyard in the US and Rajasthan, and her partnership with Bonnie and their strategies proved effective over time. They established “Marwari Bloodlines” at Dundlod to continually refine top-quality breeding stock, and created the non-profit Indigenous Horse Society to provide non-political and unbiased support for the development of breed conformation standards and general promotion of the horse. The partners involved their horses in festivals and races, and created an annual horse show with

spectacular demonstrations which they choreographed and performed.

Eventually they were able to influence the Indian government to develop a workable process for testing and quarantining horses, and eventually to lift the ban on exporting Marwari. In 2000 Francesca was finally able to export Shanti and her other horses–two stallions and three mares–to her home in the U.S. A second shipment of her horses, which was cleared and scheduled for export from India in 2004, is still awaiting release, however, because the export ban was reinstated before they could depart.

In these twelve years the partners’ tremendous efforts in promoting the breed has had amazing results in India, as reflected in the greatly inflated asking prices for even lower quality Marwari. Francesca and Bonnie believe that the increased value of the horses motivates owners to care for them better than is the typical fashion, and continue to improve the bloodlines of their horses.

Francesca estimates roughly that today there might be a total of about 12,000 purebred or part-bred Marwari horses in India. Of these, only 3,000 to 4,000 are quality breeding stock. Although these numbers are up strongly from the estimated 500-600 in 1995, the Marwari is not currently on the international Endangered Breeds List published by the U.S. organization Equus Survival Trust, which considers an “at risk” breed to have fewer than 1,500 adult breeding mares. However, in a real sense, the numbers of pure Marwari mares remaining is uncomfortably close to that at-risk category.

States Victoria Tollman, Executive Director of the United States-based, internationally-focused Equus Survival Trust, “The Marwari holds a very special place in history. To allow such a significant historical breed to slip toward endangerment is cause for alarm. The government of India and the Marwari breed organizations would show great vision in encouraging satellite herds to be established outside the country. Not only would this practice introduce the world to the wonderful horses India has produced, but more importantly, the exported horses and herds would be “genetic insurance” to come back to should the need ever arise.”

In the short term, another, more urgent need is developing as the disastrous effects of global warming trends create hardship in the arid state of Rajasthan where failing water resources are critically impacting feed availability for livestock. Knowing the situation will only worsen as the effects of the warming trends compound is of great concern to Francesca.

“It is ironic,” she reflects, “that the ancient Rajput warrior culture regarded the horse—especially the Marwari horse—as a divine creature spiritually superior to man. In today’s Rajasthan, horses are considered merely a status symbol, a priority only for the wealthy. Income-producing livestock such as camels, cattle, goats and sheep have more value than the Marwari horse, and under the pressure of faltering water and feed supplies will have preference.

“Horses are already suffering. There have been monsoons at unpredictable times of the year, creating flash floods which destroy crops before they are ready. Every summer brings higher death tolls because of increasing high temperatures, and it is no longer advisable to have foals born in the spring, because young animals can’t survive the heat of the protracted summer season. On the other hand, foaling in the winter months is hazardous because of the extreme cold at night.”

“The region has experienced prolonged droughts for a number of years. Significant levels of arsenic in existing well waters contaminate crops, slowly but surely poisoning humans and livestock with long-term use. The demand to increase irrigation because of rain shortfall further depletes the already disappearing water tables. Consequently Rajasthan is required to truck supplies of hay from the Punjab, which is a more fertile region or from other points in Central India, up to 500 miles away. Deadly molds can occur at any time due to inadequate storage. Most of this imported hay, often wheat or barley straw which is without any nutrition, is completely unacceptable by western standards. Some processed pelleted feed is becoming available but since there is no official control of ingredients, there is a significant risk in using it.”

Although she has approached the animal husbandry departments of the Ministry of Agriculture with her concerns, Francesca reports that the response was curious: “History has shown that the Marwari is a hardy animal that has survived millennia; what is so different now?” She feels more strongly than ever that the global climactic changes which are having a disastrous impact on this area of the world make it imperative that restricted numbers of the valuable breed should be exported outside their native land to thrive in more hospitable climates.

In fact, she is perplexed and frustrated by the inertia holding down desperately needed and quickly enacted changes on numerous levels. Even before her small herd arrived in the U.S., without success, Francesca has searched for an experienced U.S. horse breeder with a minimum of 20 acres who would partner with her equally to establish the Marwari here. She has had numerous offers for individual horses but she wants the herd to stay together as the family group they are. Because three million people visited the Museum of the Living Horse at the Chateau Chantilly near Paris between 1982-2002, in a great personal sacrifice, Francesca gifted her beloved ten-year-old bay stallion Dilraj to the Museum as a representative of his breed. There he takes part in the regular equine theatre performances. Hundreds of thousands of people from all over the world who would never otherwise have seen one outside of India, will see a Marwari horse.

To bring attention to her U.S. Marwari herd, Francesca has exhibited them on the East Coast, had numerous articles published (including in the June 2004 Smithsonian), and created various other publicity. Strangely, the striking and unusual desert horses frolicking at Francesca’s home, adapted to playing in the ocean and in deep winter snow, have attracted shockingly little public interest. Although there may be other options in Europe that she has seeded for which she awaits potential fruition, if she hasn’t found a committed U.S. partner by the end of 2007, she may return her herd to their homeland, to Dundlod.

There in the land for which she has such affinity, Francesca will be spending more and more time concentrating her efforts to continually upgrade the quality of the Dundlod horses. With Bonnie, she will encourage higher standards in breeding nationwide and help bring into reality such exciting projects as an academy at Dundlod. They will continue to protect and promote the welfare of the Marwari horse in any way possible and necessary to counteract the inertia that must be mobilized if a bright future for them can be hoped for.

“To know and love the Marwari is to know and love the Rajputs, for their destinies are inextricably bound,” Francesca muses. “To ride a Marwari is to realise new levels of joy that demand in turn, a receptive stillness for its appreciation. It is to view the way ahead through a pair of perfectly curved ears, gateway to the heart of India’s spiritual and ceremonial heritage.”

Francesca’s website: www.horsemarwari.com

Contact Francesca Kelly at Fkelly8254@aol.com or

508/696-8814

(To order a copy of the book

Marwari: Legend of the Indian Horse)

Contact The Indigenous Horse Society of India http://www.horseindian.com/

(IHSI is a non-profit organization which can receive

tax-deductible donations; anyone can become a member.)

Photographs by Dale Durfee www.daledurfee.com

Contact Dale at daledurfee@gmail.com.

Contact Victoria Tollman,

Executive Director of Equus Survival Trust

www.Equus-Survival-Trust.org

Contact author Kip Mistral at newhorsearts@hotmail.com