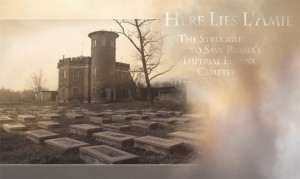

Here Lies L’Ame – The struggle to save Russia’s imperial equine cemetery – April 2006

kip mistral

We have all experienced it…we are going along, minding our own affairs, looking neither to the right nor to the left, when suddenly there appears before us something we can’t ignore, something we realize later seemed to have been put into our lives to change them.

So it happened the day that Frenchman Jean-Louis Gouraud, prolific writer, author and horseman, was doing incidental research at the National Library in Paris and stumbled onto an article from an 1860 issue of Le Magasin Pitoresque, “a sort of Science and Life of that time,” he explains. This article described a (circa) royal equine retirement home and cemetery at the Imperial Farm of Russia at Tsarskoye Selo, the summer residence of the Tsars near St. Petersburg, referring to a “veritable necropolis with elaborate monuments carrying [Cyrillic] inscriptions in gold leaf. The remarkable rest home is perfectly administered. Each animal is stabled in highly comfortable quarters and is magnificently nourished and cared for. From time to time the horses go to exercise in a large fenced meadow, just next to

the cemetery.”

His imagination captured by the idea of a once elegant equine retirement home and cemetery, perhaps now forgotten, Gouraud began to gather any additional information he could find to construct a picture of the retirement for the horses of the Tsars of Russia.

He found there was truly a very big picture. The Imperial Courts of the 18th and 19th centuries had required the use of thousands of fine horses annually as family mounts and carriage horses, providing horsepower for not only everyday business and ceremonial occasions, but war service. The massive Imperial Stables building at St. Petersburg, originally constructed in 1720-1723 by the German architect Gobel, and rebuilt by Vasilii Stasov in 1817-23, featured four long facades enclosing a large courtyard. The Imperial horses had the finest groomsmen, trainers and veterinarians to care for them, recruited from all over the world. Their tack and other caparisons were the most exquisite to be found, cared for with meticulous attention.

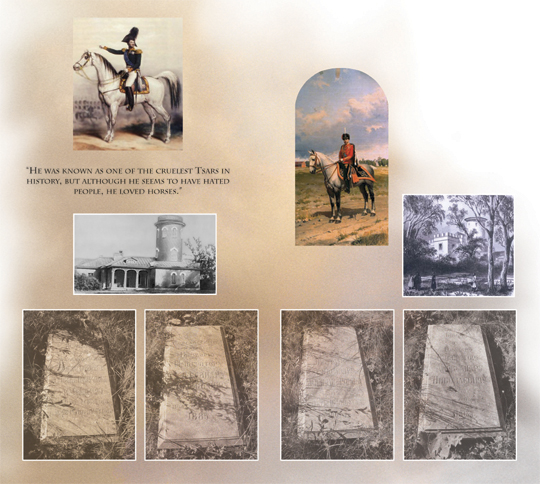

When the working lives of these honored horses were over, in recognition for their merits, the particular favorites of their majesties’ horses and chargers were pensioned at the Imperial Stables in the admittedly restricted stalls. However, when Emperor Nicholas I ascended to rule, he ordered eight older horses formerly belonging to and ridden by his brother, Emperor Alexander I, to be sent from the Imperial Stables to have special accommodation at the Imperial Farm at Tsarskoe Selo. It was the wish of Nicholas I that his brother’s notable horses, such as Amie, whom he rode victoriously into Paris in 1814 after defeating Napoleon, should have a peaceful end to their lives.

Here the elderly horses could graze in green fields during the summer—something impossible at the huge St. Petersburg facility—and be kept comfortably indoors during cold months. Yet, there was literally no room for these horses at the Imperial Farm, essentially a dairy farm that provided exclusively for the Imperial Court’s vast consumption. Accommodation for them would have to be created.

The design of smaller buildings at Tsarskoe Selo at this time was often commissioned to Scottish architect Adam Menelas, who favored Gothic styling and was appreciated for contributing to the romantic ambience of Tsarskoe Selo’s gardens and parks. In 1827 Nicholas I awarded to Menelas the design of a new retirement stable to be located to the west of the Imperial Farm. A part of the meadow to the west of the intended building was to be turned into a clover field for turning the old horses out to pasture.

“The commissioning of the rest home and cemetery was virtually the first act of Nicholas I on becoming Tsar,” Gouraud comments. “He was known as one of the cruelest Tsars in history, but although he seems to have hated people, he loved horses.”

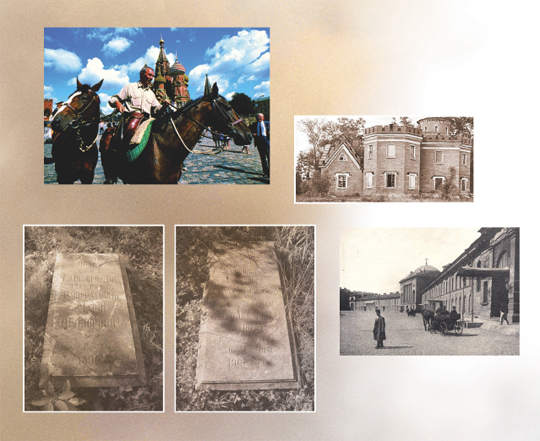

The “Retired Horses’ Stable” as it came to be known, was completed in 1830. Still standing, it is a small red brick and stone building that combines a number of architectural elements with a most unique effect. Menelas let his Gothic heart run wild. A two-story tower, or belvedere, topped by a ceramic roof, served as a pavilion. Two triangular bay windows set underneath a steeply pitched gable lit the upstairs living quarters of the watchman and stablemen. The one-story brick wing, crowned with the battlement features known as crenelations and merlons, housed stalls for eight retirement horses, as well as a room for their historic harness (which became something of a museum until the harness was removed to the Stable Museum at St. Petersburg). The courtyard was surrounded by wooden utility sheds, which have not survived.

The Tsars and their families traditionally visited their beloved retired horses at the Retired Horses’ Home, and put them to rest with dignity and grace. The Tsar himself would inspect the quality of the hay and monitored the temperature of the stable. From the Retired Horses’ Home inauguration in 1830 until the abdication of Nicholas II in 1917, 120 Imperial horses were recorded as having been buried beneath rows of marble and stone slabs honoring them by name, date of birth and death, and the Tsar they had served.

After his fascinating discovery, on his next business trip to Moscow, Gouraud began to inquire into the current status of the site. He learned it had been abandoned after the Revolution, and that in 1952 access to it had been blocked to transform it into a manufacturing shop for fireworks. Ingress and egress of trucks had destroyed many of the graves—about 30 stones. The surrounding areas had been used as a dump, and the formerly stately monument was slowly disappearing, victim to revolution, vandalism, and neglect. Gouraud networked furiously within his contacts in the Soviet publishing industry, and by October of 1988 had found in Natasha Lapchena a collaborator. Twenty years previously, Natasha’s riding instructor had shown her the abandoned retirement stable and cemetery, and she drove Gouraud and a mutual friend there. They slipped through the gates closed against the public.

They could see little at first; rundown buildings and then carved marble gravestones set horizontally, and carved in Cyrillic script, overgrown with decades of grass and scrub, unintelligible except for the numerals on the dates. Gouraud remembers, “it was a dump fenced off with barbed wire, full of broken tractors and other abandoned machinery.” Together the friends started trying to decipher the markers… “Biouta: a horse belonging to their Imperial majesties: 24 years service: died March 1834” and “Hamlet: a horse belonging to Alexander III: nine years service: died September 14, 1889.” They wandered row after row of the weathered stones. The guard who discovered them trespassing offered the information that a cleanup was planned and the site would be bulldozed.

Now having seen the site, Gouraud was hooked, and angry to learn of the prospect of its destruction. He was convinced of the significance of the Imperial retirement stable and cemetery—possibly the only one of its kind in the world—not only to the Russian people but to horse lovers everywhere. The Soviet authorities, having no interest in the affairs of the former Tsars, did not respond to Gouraud’s pleas that the cemetery be acknowledged and restored as a site of immeasurable historical value. “When they finally did respond, it was to first deny the existence of the stable and cemetery, and then to accuse me of making trouble,” Gouraud recalls. “Luckily 1988 had seen the beginning of the Gorbachev’s perestroika program. Natasha had friends at the Leningrad television station, and we got a couple of those friends to televise a story about the scandal of the impending destruction. The response was such that the authorities had no choice than to listen and act to calm things down. So, instead of razing the stable and cemetery, a couple of small steps were made to preserve it.”

The remaining gravestones were stored in the pavilion to protect them, and some general tidying accomplished. However, the lack of money to restore the monument was a critical impediment, and the project was put on hold indefinitely.

Meanwhile, in 1985, the horseman Gouraud had demonstrated his sincere engagement with the Russian culture by beginning a lengthy process to apply for permission to ride into the USSR from France. In 1990, as he continued to lobby for the restoration, his travel plan was approved and he became the first Occidental [of the noncommunist countries of Europe and of America] to be allowed to ride into the USSR since the 1917 Revolution. So, in the spring of 1990, Gouraud departed Paris on his two French trotters, Prince and Robin, and, as he says, with “the amazing luck which never deserted me” rode over 2,000 miles in 75 days without incident. Upon their arrival in Moscow on July 14th, under the Kremlin walls, Gouraud offered his saddle and saddle bags to the Museum of the Horse, and offered Prince and Robin to President Gorbachev in thanks for “changing the world, and making my journey possible.” The horses were accepted graciously by Mrs. Gorbachev.

In the years that have passed since Gouraud’s long ride, he has steadfastly supported the restoration of the Imperial Retired Horses’ Stable and the cemetery in every way possible. Gouraud has personally managed to raise about $50,000-$60,000 by, among other efforts, the sale of his books and proceeds from a magnificent equestrian spectacle charity event and the video made from it. “The Russian government still refuses to fund any restoration work. It would take perhaps $215,000 to recreate the cemetery as it once was,” he reflects. “The current administrators of the Historical Monuments of Tsarskoe Selo, and of the parks and palace there, are all motivated. Enthusiasm is no longer lacking…it is money. It is not much in comparison with the kind of money that goes into restoring other historic monuments, but I cannot raise it on my own.”

The year 2010 will mark the 300th anniversary of the construction of the Tsarskoe Selo palace and grounds. Another possibility for reconstruction funds may come in the form of a very modern solution…private real estate investment with the goal of restoring the historic monuments for this important anniversary. For example, the Imperial Farm and the Imperial Retired Horses’ Stable and cemetery are two of the historic monuments listed today on the Russian “Rost Realty” website as investment opportunities. “Realization of thise (sic) projects will give the opportunity to successful businessmen to have a good commercial and prestigious return, to get the support of the community and authorities, to help the revival of the objects from the Imperial history of Russia,” invites the charming description.

Hopefully, Jean-Louis Gouraud will not be working alone much longer.

Jean-Louis Gouraud is the author of many French equine-related books, including “Serko” a novel about the real-life exploit of the remarkable Cossack officer Dmitri Peshkov, who rode his horse Serko five thousand miles in less than two hundred days, without changing horses. Serko has been made into a feature film and released in late March, 2006 in France.)

Contact Kip Mistral at newhorsearts@hotmail.com