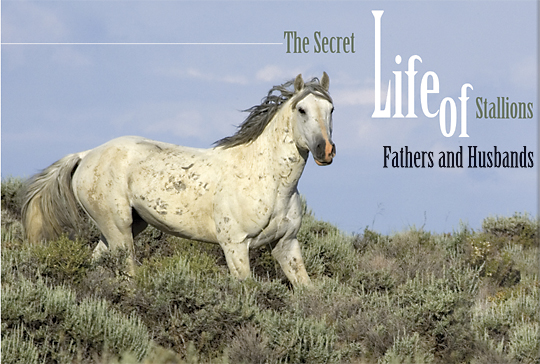

The Secret Life of Stallions – Fathers and Husbands – February 2006

kip mistral

How often do we humans assume we understand the value or meaning of something and not realize until much later that we didn’t understand it at all? Perhaps we accept such assumptions on our part because it is simple to accept longstanding notions and myths though our instinct might be warning us differently, or maybe we don’t know the questions to ask to fully understand the scope of an issue.

One assumption commonly made in the horse industry perpetuates the conviction that stallions as a group are almost invariably dangerous and untrustworthy. The stallions of certain breeds, such as the Iberian (Spanish) breeds, are generally given credit for being gentle and kind. Still, most domestic stallions endure such restricted environments throughout their lives that their frustration related to social deprivation alone is enough to make them difficult to control. If you consider the average stallion’s life—kept in a box stall with bars, led from a stall to a turnout that is remote from other horses, handled strictly at best and harshly at worst—the isolation and discipline of this kind of life would be considered imprisonment if the subject were a human.

So what are the alternatives in stallion management if we want to create a more natural living and social environment for them, whether out of compassion or knowing that a happier, well-adjusted stallion surely performs better whether he is showing or breeding? A better question is, how do we even know what natural stallion behavior is?

Where the Wild Things Go

People who have watched wild horses for years know what natural stallion behavior looks like. Mary Ann Simonds is a wildlife and range ecologist, and equine behaviorist who has studied wild horses in the field for 30 years. She will tell you that wild herd stallions demonstrate profound recognition and protectiveness of their offspring, and even the bachelor stallions that live near a band will offer protection and “babysitting” of the youngsters. Simonds breaks the myth of the savage wild stallion.

“Very few people can know what stallions are really like. There are many types of relationships among horses, both patriarchal and matriarchal. Young dominator stallions—the type that most people associate with ‘wild stallions’—might be able to break into and manipulate herds, but the mares try to escape. Mares want friendly stallions that can provide a sustainable herd environment. No one likes the dominant stallion types. Other stallions don’t get along with them, which can be important, since sometimes stallions work together to attack or drive off a stallion that they can’t live with or that can’t live within the larger community. Dominance doesn’t go well in nature.”

“And not all stallions have the chemistry to be breeding stallions. Stallions are not created equal in testosterone. There is a lot of practice “mounting behavior” in bachelor bands; they’ll all play and jump on each other, and then they’ll lie down and go to sleep. The ones who are more timid crouch down and not only don’t want to play this game with other young stallions, they will never be the ones to go after mares. A testosterone test will say there is little or no testosterone in their systems.”

“The gender birth rate in the wild is about 50-50. The truth is most stallions don’t want the responsibility of trying to go get mares and keep them. The great majority stay in bachelor bands their whole lives and will never breed a mare. And stallions in bachelor bands are simpler than people would believe. The young stallions are not asked to leave the natal band until they’re about two, when their father drives them off to start their own lives and they trail the natal band until they can join other bachelors. There is lots of roughhousing but no fighting since fighting is over mares.”

“Horses create very social interactive groups together. The youngest stallion with a herd I knew of in watching wild horses was 13-years-old; the average stallion was 19. Sustainable couples of lead mares and herd stallions stayed in the same herd for years. Stallions will even share mares. I watched two stallions born together in the same natal band, who lived in the same bachelor band for years, go on to put together a little band of three or four mares and live together very happily.”

“Stallions do have favorite mares, who typically match the stallion’s energy very well. It is very common for a stallion to have one or two favorite mares with whom they share a strong bond. Even when the mares have been settled in foal, these favorites and the stallion will continue courtship behavior, whereas the stallion will cover the other mares in the herd until each is in foal and that’s it. By the way, there is a 100% fertility rate in wild mares because they live with and know the stallions.”

“And stallions absolutely do know their own foals and make a point of spending time with them. I’ve seen stallions take their offspring out on “patrol” with them. The stallion will go to a few of their favorite mares and ask the mothers for permission for him to take their colts of weanling age—fillies too—out to check the herd with him. The mares are completely unconcerned and the youngsters come back prancing and excited, feeling very special.”

“At a BLM roundup I witnessed, one of the young stallions that had been captured was injured and seemed to be doing badly. Another stallion stayed with him to protect him, licking him, obviously trying to help him feel better. Theirs was clearly a very close relationship, undoubtedly a parental one. I’ve seen many demonstrations of affection and tenderness on the part of stallions for their family members.”

Karen Sussman, President of the International Society for the Protection of Mustangs and Burros (ISPMB) agrees with Simonds. Sussman oversees the daily welfare of about 300 wild horses that comprise three main herds roaming a preserve on the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation in South Dakota. The horses have been brought to this refuge from several U.S. locations, and she has known some of them for 20 years.

“Stallions have tremendous responsibility under pressure to manage the herd and protect the mares and foals. They are on watch at all times. I recently saw a very young foal wander out to a nearby bachelor band and her father went right out there, turned her back and then went out to take on the bachelors. On the other hand there is “Orphan Annie,” an orphan filly who is about 6 months old. One of the bachelor bands took her in and they are raising her and protecting her. Bachelors are very nurturing and if the herd sire is agreeable, they will help raise the foals. We even have foals here that go back and forth between herds and they are welcome everywhere.”

“I observed fascinating interactions one year, when two bachelor stallions came to protect orphan foals. One foal’s mother had died at his birth, and the foal was very weak. The stallions stood over him and nudged him, trying to get him up and failing that just stayed with him until he eventually died. The other foal had been abandoned by his mother. He was born with a physical defect; his mother left him and went back to the herd. The bachelors also stayed with this orphan, until a herd stallion and one of his mares whose foal had died came to pick him up. She tried to nurse him. Sadly, neither foal was saved, but there was clearly a humanitarian and very caring effort by multiple horses to try to do so. Horses are such social animals, and I believe that the way we so often deprive domestic stallions of the ability to take their place with other horses creates a lot of anger in them.”

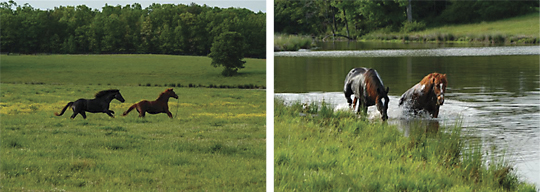

For two years equine photographer Carol Walker (whose beautiful photographs you see here) tracked a small herd of wild horses living in southwestern Wyoming. Until this past year, 1,200 horses ranged on 450,000 acres near Adobe Town until the BLM rounded up and took away 600. Walker didn’t see this band in 2005 and can only hope the stallion and his family are safe. “The horses on this land have been evaluated to prove that they have predominantly Spanish blood. This seasoned grey stallion, who is between 10-15 years, displays extraordinary affection with his family. He has one very beautiful white mare. During the time I was able to follow and photograph them the family consisted of the stallion, his mare, her new colt for the year, a yearling filly and the two-year old filly which left the family the second year I knew it. This stallion was happy with his small group. He never went out to acquire other mares; neither did he let another stallion or anything else threaten his family.”

The word seems to be spreading these days and people who not only own stallions but manage domestic breeding stock are experimenting with ways to allow their stallions to lead a natural equine life. Along with the students of wild horse behavior, they have found that contrary to the image of the dominating, aggressive stallion that many people have, stallions can make tender fathers and husbands if given a chance.

Freedom of Dogwood Farm

One example of this revolutionary philosophy can be found in operation at Dogwood Farm in Mansfield, Georgia. For twenty years Sherry Smith has imported champion dressage European warmbloods as a foundation for the dressage and jumping stock she breeds. Dogwood Farm followed standard breeding practices until they bred a colt that they named Freedom. From birth he exhibited a particularly calm, sweet temperament, and Sherry and her sister, Monica Flynn, made a bold decision. They had always abhorred the constricted lives that breeding stallions live. And, of course, owners of expensive horses dread the possibility of injury resulting from a breeding incident. But they raised Freedom with the idea he would lead a natural life for a stallion. When Freedom was a yearling, they bought another yearling stud colt for him to live and play with, and when Freedom was past two they put him out to begin running with the mares that he was intended to cover.

It was all done on faith. Monica says “Our primary motivation in the “experiment” was to create an environment where our horses could live together on their 60 acres in as natural a setting as we could provide them. Right now Freedom has a herd of four mares, and he has never put a mark on any mare. When a mare is ready to be bred, he has never shown any aggression or dominance toward her. She tells him when she is ready; he watches and listens. He has never had the opportunity to learn from observing mating behavior, it is instinctive. Freedom has been with these mares all along so they feel a real bond with each other. He enjoys his companionship with a mare. He licks her legs and breathes her mane. When he is breeding a mare he has such a soft eye, and he caresses her, standing afterward with his head lightly across her back.”

“My own mare, Future, was considered to be barren, and she had been running with Freedom and the other mares since last spring. She wasn’t cycling during that time. One day last summer, she was on lead in the pasture but got away. Freedom tried to get her to stop running, but she ran from him all over the acreage until he eventually cornered her in the lake. All he was doing was getting her to submit to his direction; he never touched her. Standing there in the lake, Future started softening to him. It was truly a symphony. Then he was attracted to our human activities near the house and walked away from her over to us. She trotted after him of her own will! In December she finally allowed him to complete the mating cycle…in the lake where he first wooed her. This is a sensitive mare who seemed to be frightened of the breeding act, but Sherry and I have both noticed that Future seems more confident in herself, with a certain new look in her eye, and she is behaving in a more assertive way with the other mares.”

Freedom has settled all of the other mares and Monica is waiting to find out whether Future has conceived. “When the mares foal, we will bring them in since we don’t know if the mares will let us have access to the foals if they foal out in the acreage. Then we’ll put the mares and foals out with a fence between them and Freedom to see how they behave together. Freedom has been teaching us; he is showing us the way. We were the blank slate.”

Empowering Stallions the Epona Way

The black stallion and two black mares grazing in the pasture at Apache Springs Ranch near Sonoita, Arizona, are the renowned Midnight Merlin, the Tabula Rasa, and the Comet made famous by the work of author, speaker, and horse trainer Linda Kohanov. In 1997 Kohanov founded Epona Equestrian Services, a Tucson-based collective of riding instructors and counselors exploring the healing potential of working with horses. Quickly assuming her place as a noted pioneer in the field of equine experiential learning, in 2001 she published the legendary The Tao of Equus: A Woman’s Journey of Healing and Transformation Through the Way of the Horse, followed in 2003 by Riding Between the Worlds: Expanding Our Potential Through the Way of the Horse. It is a fact that the work of Epona Equestrian Services and both of Kohanov’s extremely successful books have been instrumental in paving the way for our rapidly expanding understanding of the complexities and richness of the horse/human relationship.

A case in point: Merlin, a formerly violent and dangerous Arabian stallion, came perilously close to being destroyed before he was given to Linda Kohanov some years ago. Today a peaceful Merlin lifts quiet, friendly eyes from his important business of eating to look thoughtfully into the visitor’s face. Yet for years after coming under Kohanov’s protection, this stallion of obviously noble character maintained a stance of apprehension, as tightly coiled as the proverbial spring, his trust and behavior clearly damaged by his experience with humans. Of the things that are known about Merlin’s previous life, it has been told that he lived for an indeterminate time in a stall with his head tied between his forelegs—a sickening, unforgettable life lesson about submission.

“When I first met Midnight Merlin,” Kohanov writes in The Tao of Equus, “no one was sure if he would ever be able to break the cycle of fear and aggression he exhibited seemingly without provocation. Hypersensitive to the slightest gesture or change in tone of voice, he had been known to take even the most benign request for cooperation as an affront, exploding without warning into a violent rage that left most people he encountered shaking in their boots. Somewhere along the way, the stallion had come to associate his phenomenal vitality with anxiety, fear, and unbridled rage. The very expression of his life force was routinely experienced as a threat that plunged him inexorably toward the flight or fight sequence; preparation for emergency, uncontrollable impulses to flee or fight, disorganized frenzy or dissociation [terminology that defines a separation from psychological association with others to avoid the anticipated experience of being harmed].”

Merlin has much in common with many domestic stallions in his experience of his own life. In the U.S. today, stallions are typically branded as being potentially dangerous and fearsome, guilty until proven innocent, as in “never trust a stallion,” and “never turn your back on a stallion.” But Kohanov is convinced if stallions are behaving violently, this is in most cases born of tremendous frustration, less of it sexual than one would believe.

If he is a breeding stallion—and Merlin had been bred—he is never allowed to socialize with other stallions and probably even has limited exposure to geldings if any at all. And of course, the only time he sees mares is when they are the object of his sexual attention. Kohanov has come to believe that the average stallion’s lack of opportunity to participate in normal herd behavior creates and compounds such anxiety that the prospect of even being near any other horses is emotionally overwhelming. It can be difficult or even impossible for this stallion to control himself, let alone allow himself to be controlled.

Kohanov feels that these typical circumstances prevent a stallion from thriving, a word used infrequently these days, that means to grow and prosper richly. Applied to a stallion, the use of this word would presume that we think the quality of his life is important. Certainly this is true of Kohanov’s perspective. In time, as part of her continuous effort to understand Merlin and find opportunities to improve his sense of enjoyment of his life, she dared to gradually bring the stallion and several of the Epona herd members together in social contexts. In an amazingly short time Merlin and the black Arab mares Rasa and Comet were living happily together in the grass pasture.

“It was fascinating to watch their styles of relating develop within the small herd structure, and observe the way they chose to spend time together,” Kohanov reflects. “Rasa and Comet have very different personalities and even breeding styles. Rasa and Merlin had bred before (resulting in the 2002 colt Spirit), but Rasa, the queen of Merlin’s harem of two, doesn’t seem to particularly enjoy even the mutually desired pasture breeding act and is happy enough to “have it done and over.” But Comet does enjoy being with and mating with Merlin, and flirts with him, encouraging him to linger over their time together, so between the two of the mares, Merlin has a more rich sexual and emotional life. There is little tension between the mares; Rasa knows she is the honored queen, and Comet knows she is the adored concubine.”

Merlin can leave his mares to go out of the pen and be worked, or one of the mares leaves the other two horses, with no frantic, anxious behavior when one departs. They know they live together, and they know they’ll return to each other in time. “They pay complete attention to whatever task is required of them–are fully present in their training or whatever else they are doing–and they are also glad to see each other afterward. When they are with humans, they enjoy that. Then they can come back to the pasture and be horses together again. There is an excellent natural balance,” Kohanov smiles.

With Merlin’s new state of relaxation and confidence in himself as a horse, and as a stallion, he was started in a unique training program. So successful has been his rehabilitation that, armed with lessons learned from her experiences with Merlin and other stallions, including Merlin and Rasa’s own son Spirit, Kohanov has decided to create a unique Epona program for socializing stallions with their owners/handlers. The program is intended to help stallion owners create living environments that will help stallions not just survive, but thrive.

A New Paradigm

In the end, the accounts of wild horse experts prove over and over that stallions make tender, attentive fathers and husbands, demonstrating easily recognizable gestures of affection that any human could identify with. And a new paradigm is being forged by compassionate stallion owners who know that their stallions live frustrated, unfulfilled lives, and are determined to change that. Pioneers such as Linda Kohanov and Dogwood Farm are committed to making the quality of their stallions’ lives a priority, taking the time necessary to carefully develop a herd-life for them and their mares so none of them will be emotionally deprived, and trusting that foals born and raised in a natural, family environment will have a huge psychological advantage. Lucky stallions like Midnight Merlin and Freedom no longer need to keep their secrets.