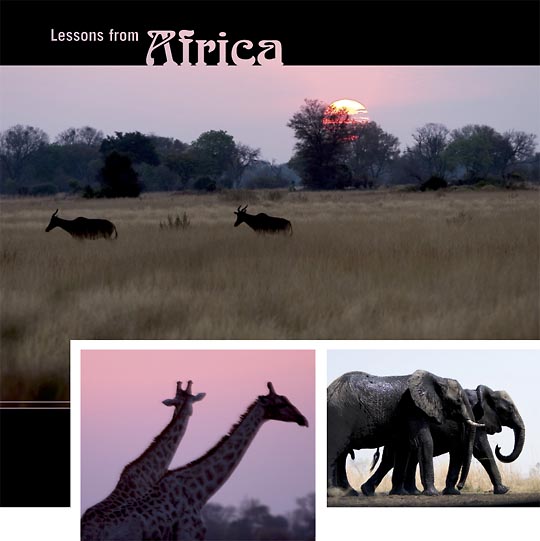

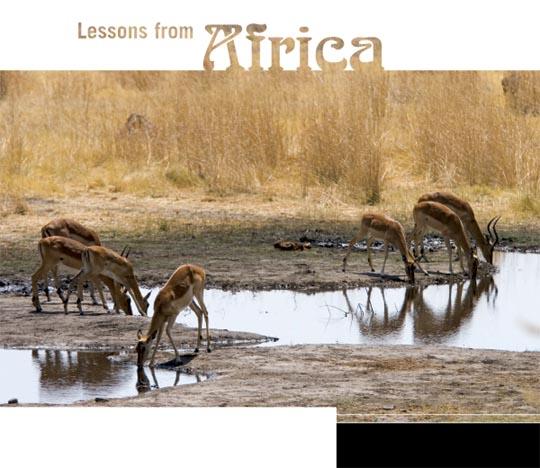

Lessons from Africa- December 2007

“For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings, they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life, fellow prisoners of the splendor and travail of the earth.”

—Henry Beston, 1928

Evalyn Bemis

Photos by Evalyn Bemis

Sometimes the best way to improve your relationship with your horse is to get a little perspective. I recommend travel.

We went to Africa and returned with it indelibly inked in our hearts. We traveled to see a wild place and came away with invaluable lessons. We witnessed the uncertainty of life and were reminded to enjoy the good in every day. What we consider the bare necessities here – shelter, food, security – were not a given there.

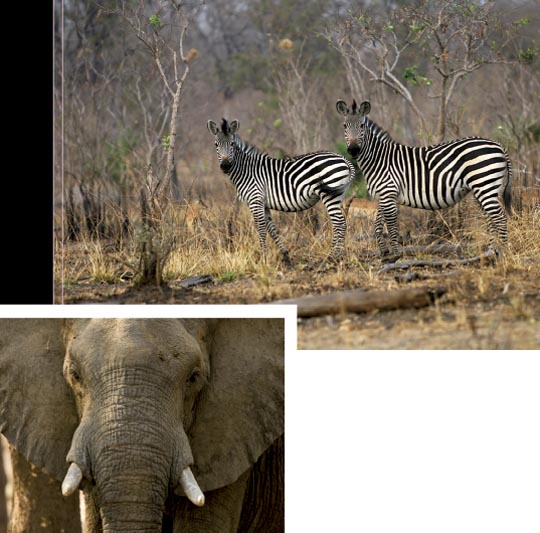

The grass and underbrush around Zambian villages is regularly burnt to the ground to remove hiding places for deadly snakes and hungry lions. Elephants are kept away from the ripening millet fields by women who keep watch all night and have only tin cans to bang for noise. The success of the crop means the difference between feeding their families and going hungry.

The village of Mkasanga is lucky to have 3 or 4 community water taps for its 1000 inhabitants. They no longer have to carry water a mile or more from the river. If someone has a few chickens to sell in the market or to trade for some supplies, Mfuwe is a day’s bike ride away. A doctor visits the village once or twice a week.

One of our guides at Tafika Camp was Alex Phiri. Alex went to school in Mkasanga and then on to guide school with a scholarship from Tafika’s owners, John and Carol Coppinger. He received his guide’s license in April, and began work at the start of the dry season. He knew he was very fortunate.

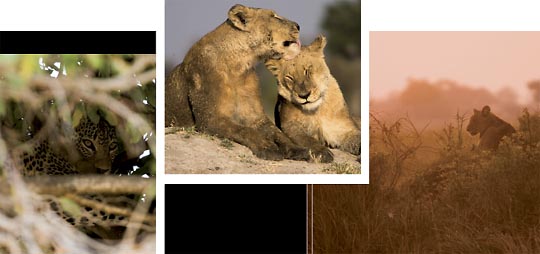

We went on a game drive with Alex. His keen young eyes spotted a leopard in a tree, holding her freshly-killed impala out of reach of the hyenas. Her two cubs were hidden somewhere nearby, waiting to be fed. Perhaps the hyenas had hungry pups as well. We rooted for the leopard to retain her kill.

Our Chikoko Camp guide, Stephen Banda, told a story of seeing an elephant with a wire snare around its foot. He was out with Steve Irwin, the legendary crocodile wrestler from Australia, and Steve was very upset by the elephant’s plight. He suggested that they tackle the elephant and try to remove the wire. Stephen Banda was sympathetic but more realistic about their chances of success.

When we came upon the One-Eyed Pride, so named for the matriarch, the family appeared thin. Justice, our guide at Kwara, thought they hadn’t eaten in days. Yet the six of them seemed content to snooze atop an ant hill in the early morning sun, knowing the night would be their time to hunt. The tattered old lioness groomed her daughter while they rested.

A solitary lion was within our camp perimeter in the Okavango Delta. Apparently he had been around for two months. He turned up with a terrible wound on the inside of his thigh, the result of a clash with a buffalo. None of the guides thought he would survive but his brother brought him food. When we saw him the wound was still visible and he walked with a limp but his weight looked good. He walked around at night, calling to the pride. It was an eerie thing to lie in bed, in a room made of canvas, listening to a melancholy lion.

We saw an impala with a broken leg, left behind by the herd, sure to be dead by morning. A warthog was missing a foot, perhaps left behind in a snare. An egret had a broken beak, which meant it could no longer spear the fish that it still vainly stalked. It was hard to witness these things and accept that we could do nothing to help.

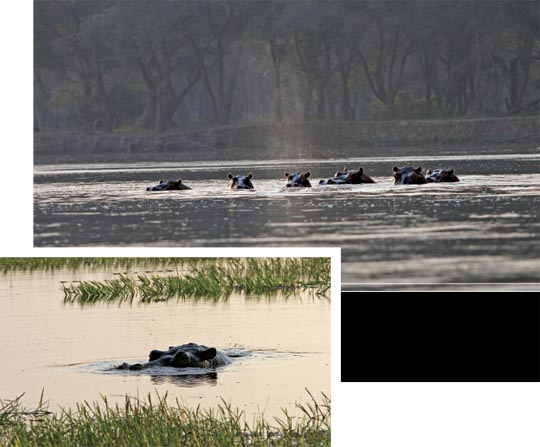

At Old Mondoro in the Lower Zambezi National Park, Norman the wild hippo had learned that he didn’t have to fight other males for a place in hippo hierarchy in the river if instead he slept onshore. Most hippos graze on land at night and rest in water during the heat of the day. Norman spent his days on an island close to camp. At dusk he crossed the river and climbed the steps up the bank from the boat dock to return to his sleeping spot next to the manager’s cabin. Norman felt safe in camp but lived alone as a result.

Guests at the lodges seemed to relish telling “campfire” stories. It was hard to distinguish the truth from the embellishments. My favorite scary story was the one about two game wardens and their wives on a fishing outing on the Zambezi. Their boat was turned over by a hippo and they were far from shore (the Zambezi is the 4th largest river in Africa). They found a shallow sandbar in the river where they could stand in about a foot of water, and hoped they would be safe from crocodiles. The sun was going down with no rescuers in sight, so one of the men decided to swim for it. Just as he was reaching the far bank, a large croc plunged into the water and grabbed him by the arm.

A crocodile usually kills by pulling its victims under water and rolling very fast. Sometimes a limb gets torn off in the process. Knowing this, the warden wrapped his legs around the body of the croc. He also knew that if he could pull on the crocodile’s tongue, water would flow down its throat and the beast would have to release him to prevent its own drowning. He had the presence of mind to do this while being tumbled around underwater. Remarkably, he got away and crawled out onto the bank.

The next morning fishermen discovered the three who were still stranded on the sand bar, cold and afraid but otherwise unharmed. The story ended with 15 minutes of fame on BBC World News.

We didn’t have a brush with death but there were a few moments of mild terror. One evening as we were wending our way back to Old Mondoro, the safari vehicle had a flat tire. No big deal, right? The guides are skilled mechanics among many talents, right? However, in this case, there seemed to be a lot of fumbling around with the jack. The bush is very dark when there is no moon and no street lights. Actually, there is no street. Just a lot of dark in which one can imagine seeing glints of eyes and teeth.

The guides didn’t want to make a big deal of the situation, except they kept telling us to stay close to the vehicle in the headlights. They whispered urgently on the shortwave radio handset, “Come in, Mondoro, Mondoro,” and then spoke in one of the 72 languages used in Zambia. Meanwhile we were thinking about the headlights draining down the battery, which would leave us seriously stranded. After several more attempts and a close call with the vehicle almost dropping on its axle, the tire got changed and we were on our way.

Our last night in the Okavango, I broke the cardinal rule of safety in the bush. We were walking back to our tented room after dinner, shining the pale beam of our little “shake-to-recharge” flashlight into the brush along the path. Suddenly our guide Justice stopped and said “Ele”, as a lone bull swung his head and trumpeted a warning at us to not come any closer. I turned 180 degrees and bolted, my camera backpack suddenly light as a feather. Justice and David simultaneously said “Don’t run!” I stopped, embarrassed but relieved that there was no charging elephant behind me.

Justice decided that the prudent thing to do was detour through the kitchen tent. At the back side of it there was a mess of cans and bottles strewn about the dirt floor, from a hyena rummaging in the garbage. By the time we got back to our room, we really liked the idea that it was raised 8’ off the ground –like being up a tree.

Once we were safely inside, we laughed until tears streamed down our faces. I made David promise not to tell on me.

We left camp after lunch the next day, traveling 36 hours to return to New Mexico. It was wonderful to be home with the dogs and horses but hard to quit Africa. Pablo barked at me when I tried to imitate the lion’s roar and the hippos’ rumblings. I didn’t want to forget what they sounded like.

I have more sympathy now for my horse when she spooks at a shadow or the rustling of leaves, having witnessed nature’s wild side. I better understand the importance of establishing trust and respect in the training process, considering what an animal gives up to accept my control. We are having much more fun and success together.

I went to Africa and didn’t see or think about horses for three weeks. I am grateful to have experienced a place where life is still wild, with all its harsh realities and beauty. Home again, I feel blessed by my relationships with animals and all that they teach me.

To find out about Botswana and Zambia, visit www.expertafrica.com. Expert Africa is a travel services company based in London. Chris McIntyre and Anna Devereux were knowledgeable and helpful in booking our trip. Babette Alfieri, Africa Calls Ltd, lives half the year at Kuyenda Camp in the South Luangwa National Park in Zambia and half the year in Santa Fe. She made many good suggestions and can also make travel arrangements. Africa Calls can be reached at 505-982-1976.

To see more photos of Botswana and Zambia, visit the author’s website at www.imageevent.com/evalyn87508.