Stal El Paradiso – A quest for grace in classical Equitation – August 2006

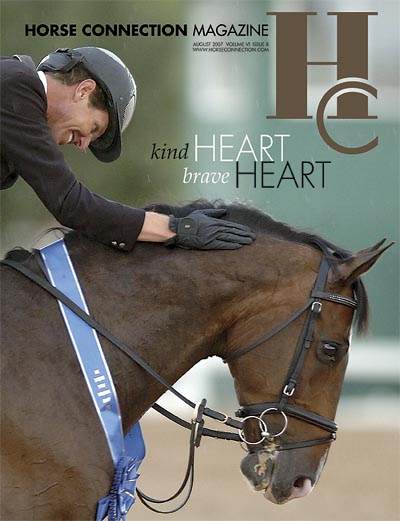

kip mistral

In Arthurian legend, the sacred cup known as “The Grail” was sought by the Knights of the Round Table as the object of an extended or difficult quest. The story of the quest for the Grail has become a metaphor for an idealistic, intellectual or spiritual goal sought after for its great significance, insinuating a long, wandering voyage usually marked by many changes of fortune. Such an odyssey is meant to challenge the quester—spiritually, emotionally, physically—to his or her limits of devotion. This quest is very personal indeed.

Finding Meaning in Today’s Horsemanship

Ellen Schuthof’s small, jewel-like equestrian facility near Amsterdam, Stal El Paradiso, represents the outward expression of such a personal quest. Stal El Paradiso (“Paradise for Stallions”, she smiles) is fundamentally Schuthof’s laboratory for discovery and experimentation in classical equitation. But, one might think, isn’t that a paradox? Isn’t the whole mystique of classical equitation that its tenets are written in stone? That its traditions have come down through the Greek general Xenophon, channeled in time through western Europe and the great court equitation schools of France, Portugal, Spain and Austria, and left unchanged in philosophy and technique?

Schuthof’s fearless inquiry into the ideals of today’s horsemanship questions whether our assumptions about these traditions might have become confused, or at least reductive, distilled too long over centuries of practice, teaching and learning. And she has the light of the quest for the Grail in her penetrating green eyes as she contemplates the few teachers remaining today who can rightfully claim an authentic lineage of true classical academic dressage. At a time when not only the delicate points of truly fine riding are lost on most equestrians, fierce controversy is currently being waged about written rules versus actual criteria for performance. Even the physical welfare of over-controlled, stressed dressage horses straining to win in competitions across the world is being questioned.

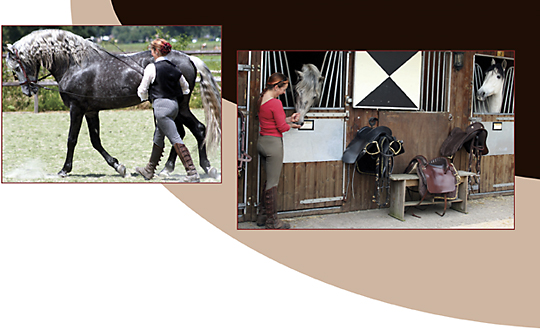

Schuthof’s objective is deceptively simple. She wants to find ever more gentle and tender methods of handling and “training” a horse that condition him to be exquisitely light and flexible in the hand, whether on the ground or in the saddle. Of course this horse will be properly and gradually gymnasticized so he can develop the strength to master important exercises. Such exercises in turn allow him to comfortably maintain self-carriage in trained movements and give him the confidence to be relaxed, to enjoy his schooling and performance, and most importantly, trust and like his handler. He may never see a show ring and in fact, the “master” training that Schuthof seeks everywhere is not for the show ring. Her highest principle is to seek grace and beauty in the relationship between the horse and human, through the advantages of academic equitation training. She wants the ambrosial, blissful waltz of two beloved partners.

Schuthof can see, looking back, that what has become a methodical, full-scale search began naturally when she was a small girl, learning to ride first on bareback ponies, then horses. As she began and continued her formal studies over the years in jumping and then in dressage at sixteen, she realized there was a great deal lacking in the training, practice, and competitions. The horses were not happy, and the riders and trainers were not happy, even at the prestigious circa 1882 Hollandsche Manege where Schuthof kept her horse and trained. Preparation for events or shows was stressful, not fun, and she felt the horses were merely tools implemented by the humans to win in competitions. Schuthof had such doubts as to the justice of these lifestyles for the horses, and the overall meaning of the pursuit of the sports in general (sport as opposed to art), that she completely quit riding several times. But her passion for horses couldn’t be denied, and she would return to lessons at equestrian facilities, again only to find the same joylessness.

Searching the Heart of History

Finally, Schuthof acknowledged to herself two things. She would not be happy until she had a dancing, elegant Spanish horse, the type her acquaintances in the horse world would laugh at, calling it a “circus” horse in an equine environment that allowed for only interests in state-of-the-art jumping and competition dressage. And she would not be happy until she learned the beautiful equitation that could allow this special horse to be proud and happy and eager to be ridden and handled by her. “I had to do it my way,” she shakes her head, “I knew that what I wanted would not be understood by anyone I knew, but I had to do it my way.”

So she began to look simultaneously for her magical horse and for this exquisite equitation. Her search took her to not only other countries but more than two thousand years into the past.

Schuthof discovered that the balanced, responsive physical relationship between horse and human that she instinctively learned from her early bareback rides had a formal precedent as a pan-European cultural heritage. Historically, even predating the formal, elaborate court equitation of the 17th-18th centuries that evolved from movements developed for war, the same training techniques were used for horses fighting bulls and working cattle to develop suppleness, impulsion and maneuverability derived from powerfully collected haunches.

The goal to ride one-handed meant that you had the other hand free to hold your weapon or tool, and most importantly you had the horse perfectly between the reins, between your legs, in the front of your seat towards the hand, and had the horse in perfect collection. As schooling progressed from the walk to trot to canter, to piaffe and passage, you and the horse learned to keep this contact, balance and collection even in jumps. So when you come to a real situation—war, for instance, or evading a bull in the field—the horse would be part of your own body.

A Lesson is a Lesson

When Schuthof brought her young Andalusian stallion, Fernando, home four years ago as a “clean slate,” and a fresh start for both of them, she renewed her effort to find the best in classical training techniques for him. Being multilingual (fluent in Dutch, German and English, with French and Spanish) she was able to search a wide radius in Europe, Holland to Belgium, Germany, Austria, Portugal, and Spain, to watch demonstrations, workshops and clinics. She observed the training at the Spanish Riding School in Vienna and the Real Escuela Andaluza del Arte Ecuestre (Royal Andalusian School of Equestrian Art), and took lesson after lesson. “I discovered there were a lot of instructors who said they were “classical trainers,” but I found that they were not teaching the part of classical riding that I was looking for. The training was competition-oriented. But, nevertheless, every lesson was a lesson.”

“During this period, I rode with Belgium’s John Van Doorn, who helped me to ride with my seat, and without reins. I trained in Spain at El Ranchito where I learned the Spanish walk and passage, and with the Spaniard Sebastian Fernandez who showed me how to feel and express pride. In Holland I studied with Piet Bakker who taught me the long reins, Marion Klundert who worked with me on freestyle, and de Recht who drilled me on technical aspects of the movements. I rode with the American David de Wispelaere, who is based in Germany, and from him I learned about paying attention to my breathing. I had lessons with Joao Rodriguez of the Escola Portuguesa de Arte Equestre (Portuguese School of Equestrian Art). All this time I was watching videos, reading books from all countries, talking to every one I could. I brought the best I could to Fernando.”

One day Schuthof was introduced to academic and baroque equitation in the form of Danish trainer Bent Branderup. An equine magazine cover featured Branderup on his blind Knapstrupper stallion Hugin in piaffe with the reins dropped. “I thought, if this is possible why are we doing anything else with our horses?” She traveled to watch Branderup ride in a clinic, and then became a regular student for two and a half years, even trailering her horses 12 hours one way to his training facility in Denmark. “Bent taught me to ride one-handed, and with more flexion in the horse. He helped me develop my independent seat even better, and taught me a different use of my seat bones. In Spain I was taught to use my upper body weight more—you see this also in the bullfighting there—but the seat Bent teaches is very subtle.”

She acquired several magnificent baroque equitation saddles that have flexible trees; one has a leather tree to provide an even closer contact. The intricately-designed baroque stirrups from Spain and Portugal are not only visually glorious, but also balance the saddle and provide more support under the ball of the foot. With this combination of saddles, Schuthof can match the needs of the horse and rider on any day. Her second Andalusian stallion, Pícaro, joined Fernando two years ago, and she can use all of these remarkable saddles on both of them.

In schooling, both stallions are happy, attentive, challenged and enjoying the work. Sessions come in short increments, lightness and relaxedness emphasized at the same time that strength training is implemented. Lessons are 20-30 minutes, and the horses learn exponentially, becoming ever more smooth and confident, offering movements eagerly because they are enjoyably challenged. The brief periods of quietly intense schooling are an excellent workout, yet the comparatively short lesson ends with an energetic, excited horse who is not weary and stressed from grinding around a dressage court for 50 minutes doing endless repetitions. Schuthof spends a great deal of time doing work in hand and long reining, so the horse has mastered a new skill before the rider even mounts.

“The Horse is Always in This”

“It’s all about patience and lots of respect,” she reflects. “When you do it the right way, you have a very healthy and powerful horse when his body is given time to develop. A horse is so eager to cooperate and so loyal; this is why so many horses are ruined at a young age. In that sense the true classical education can be so good for the horse, but it takes time. It takes time for the body to grow and the spirit needs time to grow, too.” In 2005 she was asked to give several demonstrations of classical training, ridden and in-hand, at several venues, which so impressed audiences that breeders, owners and potential students sought her out immediately. Schuthof has developed an enthusiastic following. Lusitano breeder Huizink comments “Our search for suitable training for our three year old stallions led us to El Paradiso, one of the very few places in Holland where horses are trained according to the fundamental principles of the classical school. Ellen Schuthof worked with them exclusively from the ground, training them to carry themselves correctly, with the charisma of a proud horse, and to prepare them for the day they will carry the rider.” Student Natascha Anemaet enthuses, “I travel every week 120 kilometers (75 miles) each way to take training and it’s worth all of it!”

A common theme in her clients’ comments reflects admiration that Schuthof has invested so much time and energy in seeking out the best of the old—and the new—and in learning for herself. But she never rests. Currently she is training with two Portuguese masters, Pedro de Almeida, a favorite student of the late Portuguese classical master Nuno Oliveira, and Francisco Bessa de Carvalho, a rider and trainer at the Escola Portuguesa de Arte Equestre.

With her client base building quickly, Schuthof is looking at expanding her facility, and in her usual intrepid style, she is thinking big. She is exploring special properties for a site where she will ultimately integrate an academy for baroque equitation, provide horse boarding and living spaces for visitors coming for lessons, programs or apprenticeships, a restaurant from which observers can enjoy watching the academy’s trainings or staged performances accompanied by live music, a classical library, old gardens and grounds and elegant buildings…all of which will reflect Schuthof’s quest for grace in the human and horse relationship.

“I am exposing my feeling in this dream…with the horses, with the music, with the academic education, with the beautiful tack, with the books, with the high ceilings, with the senses, lighting and incense…it is beauty. The horse is so special that it deserves a special place and treatment. If everyone knew how special horses are, they would agree, and that is what they would see. The horse is always in this for me. If I can do it, I will show what is inside of me.”

Visit and contact Ellen Schuthof at www.el-paradiso.nl.

Contact Kip Mistral at newhorsearts@hotmail.com