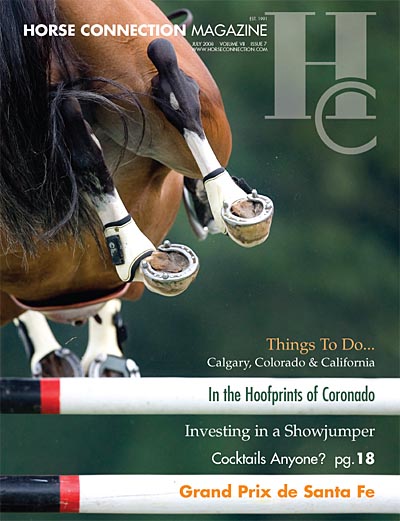

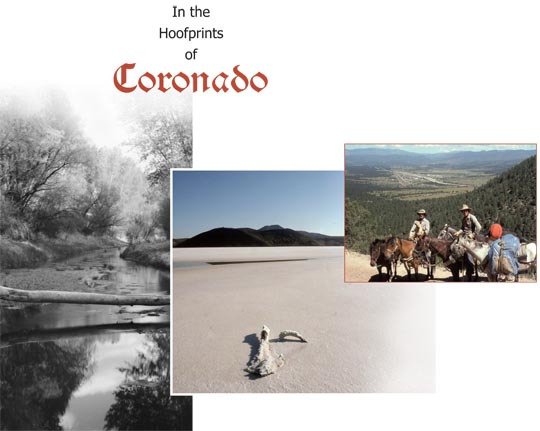

In the Hoofprints of the Coronado- July 2008

Tom Moates

Photography by Walter Nelson

“I was a complete dude,” admits Long Rider and well-known writer Douglas Preston. Given his accomplishment, it is a truth difficult to believe.

“I was a complete dude,” admits Long Rider and well-known writer Douglas Preston. Given his accomplishment, it is a truth difficult to believe.

Without previous horseback experience, a 1,000 mile, brutal, middle-of-nowhere, get-yourself-killed, deserts-of-the-American-southwest Long Ride became Preston’s hellacious introduction to the saddle. The year was 1989.

The modern day Long Ride through the desolate desert region from near the Mexican border of Arizona to Santa Fe, New Mexico firmly established Preston in the ranks of the Long Riders’ Guild, an international association of equestrian Argonauts who hail from 38 countries. Each LRG member completed a continuous horseback journey of 1,000 miles or more. Likewise, his adventuresome equine endeavor was again internationally recognized when he was made a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

Even among such notable company, this Long Rider’s expedition ranks highly in the categories of sheer physical near-impossibility and historical significance. It is especially remarkable given the journey’s location and timeframe of the latter 20th century, when North American horsemanship underwent previously unparalleled voluntary confinement to popular indoor arenas and tiny round-pens as opposed to seeking challenging rides to horizons hundreds of miles distant.

The inspiration for this equestrian trek was its previous history and documentation. In 1540, a Spaniard, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, led the first European expedition into the heart of what became America in search of the fabled “seven cities of gold.” Coronado amassed 300 Spanish soldiers, more than 1,000 Tlaxcalac Indians, and a sizable herd of livestock and led the expedition north from Mexico into the unforgiving desert land of the southwest.

That historical Long Ride was the first to penetrate deep into the American interior by Europeans. Historians have expended furious energy and considerable quantities of ink over its details for centuries. The expedition encountered several sizable Indian settlements, though none glittering of gold as reputed. The journey was thus a failure in the eyes of the Spanish at the time. It remains, however, one of the world’s all time major cultural crossroads. It was the flashpoint at which Europeans and many Native American societies made first contact. Horses, having disappeared from North America for thousands of years, were reintroduced to this part of the globe by Coronado’s expedition. The continent’s radical alteration and race to the modern era in essence was sparked by this event.

The second documented Long Ride through the country that Coronado first explored was initiated by the mind that later produced such celebrated thrillers as Relic and Tyrannosaur Canyon. For Douglas Preston, riding this route ultimately would help ignite his distinguished career as a New York Times best selling author. It also provided for his equestrian education, and fashioned him as a horseman in a gritty, seriously old- school, hombre way.

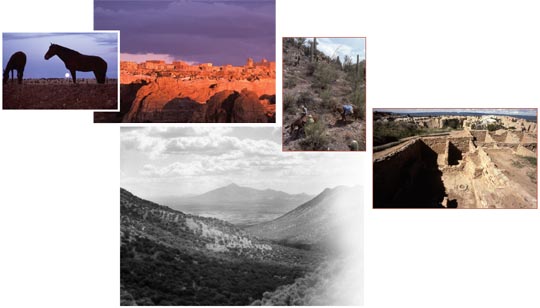

Preston set out to experience first-hand what the earlier horseback expedition encountered. It proved an easy task, since that country remains virtually unchanged since Coronado’s time—it is every bit as inhospitable, barely penetrable in places, short of water, and extremely deadly.

Preston set out to experience first-hand what the earlier horseback expedition encountered. It proved an easy task, since that country remains virtually unchanged since Coronado’s time—it is every bit as inhospitable, barely penetrable in places, short of water, and extremely deadly.

“I wanted to write a book about Coronado,” Preston says. “I just didn’t feel I was getting the real history. I wasn’t getting the grit of it. I wanted to write a book that would capture it. The problem with historians is that they don’t get out and do it. They haven’t experienced it. These professors who wrote about Coronado knew absolutely nothing about horses or the terrain.”

At the beginning, Preston was himself a New England writer and researcher (that’s bookworm, not seasoned equestrian adventurer). Working too many hours for too many years inside the American Museum of Natural History in New York City inspired him to get out there and make the ride to better know for certain just what must have happened. He struck out from the concrete confines of that academic crypt with all his worldly belongings piled in a Subaru and drove to sunny Santa Fe, New Mexico, following, he says, the advice of S. J. Perelman that “the dubious privilege of a freelance writer is he’s given the freedom to starve anywhere.”

Sure enough, starvation circled him like a buzzard, but on this horseback adventure it proved to be one of the more trivial predicaments he encountered. More than once, the journey nearly killed him and the traveling companion he talked into accompanying him, distinguished western photographer Walter Nelson. And then there were the difficult parts of the journey.

“The hard part isn’t riding,” Preston reflects, “the hard part is when you’re not riding.”

Where does one tie a horse when there is nothing but barren earth from horizon to horizon, for example? One cannot ride a horse endlessly in general, let alone in hot, dry desert conditions. There were times when they had to stop and rest, consoling themselves with no certainty of water ahead in the near future. Of course, no roads or feed stores dotted the area…nothing was there but perhaps a few predators, the stars, and thorny scruffy brush to keep them company while they sat in the dust, hoping to make it somewhere for the next drink and meal suitable for horses primarily, and humans if lucky.

Somehow, rather than becoming a sun-burnt pile of bones in one of the most remote places on earth (as predicted by several seasoned cowboys from the area), the men completed the Long Ride. Preston transformed personally. Incredibly, he had no previous horseback experience when he set out to complete as difficult a journey as North America has to offer. The writer, while in the saddle all day every day, soon became a horseman…and it’s a good thing, as there existed no escape route or life raft from this adventure.

Like Coronado in 1540, no golden cities awaited Preston in 1989, but he did discover some nuggets of truth out in the desert. Preston recorded information about many factors of the route, such as geography and availability of water, that directly relate to horseback travel. These provided new insights into understanding which routes could, or could not, have been taken; insights only discenarble in the field on a horse, rather than speculating and debating on those routes by studying maps.

Preston’s new equestrian-based skills and findings merged with his existing academic abilities. Upon completion of the journey, he wrote the definitive book on Coronado’s famous first Long Ride entitled, Cities of Gold. It is the only first-hand modern account of horseback travel on the conquistador’s route. The only other texts were those surviving from the original journey, penned mostly by a member of the expedition named, Pedro de Castaneda.

“Many historians have gone right on writing about Coronado since Cities of Gold came out, but have completely ignored it,” Preston says, chuckling. “Horses don’t fit with their lifestyles. They tend to be sedentary people. They are very judgmental of what Coronado did [violent encounters in particular] not taking into account the desperation for food, and for food for their horses.”

“Many historians have gone right on writing about Coronado since Cities of Gold came out, but have completely ignored it,” Preston says, chuckling. “Horses don’t fit with their lifestyles. They tend to be sedentary people. They are very judgmental of what Coronado did [violent encounters in particular] not taking into account the desperation for food, and for food for their horses.”

Coronado wasn’t the only trail blazer beckoning Preston into a saddle in the desert southwest. “I was definitely inspired by Clyde Kluckhohn at Harvard,” Preston explains. “As a young man he made this ride back in the 20’s to the Rainbow Bridge.”

The ride Preston refers to is immortalized in the book, To the Foot of the Rainbow, written by Kluckhohn, (published by LRG Press: www.horsetravelbooks.com). Kluckhohn became a preeminent professor of anthropology in America in the mid-20th century, but as a young New Englander convalescing in the arid climate of the American west, his curiosity drove him into the saddle for a historical Long Ride. Much like Preston, from the east and without equestrian experience, he saddled up and headed into the unforgiving desert on adventure. Kluckhohn sought a legendary natural stone bridge that reputably existed on Navajo lands. He became the first white man to ride to the remote sight and see the incredible rock formation.

“Kluckhohn was my father’s professor,” Preston explains of their personal connection. “My father majored in anthropology, that’s how I came to know about him. I read the book.”

Preston has continued to ride since his initial horseback experience in 1989. In 1993 he took another Long Ride. This one was 400 miles across Navajo territory in Utah and New Mexico along the Moonlight Trail with his fiancée, Christine, and her daughter, Selene. It is the bases for another book, TALKING TO THE GROUND: One Family’s Journey on Horseback Across the Sacred Land of the Navajo, published in 1995 by Simon & Schuster.

Preston says he has taken many other trips on horseback, and prefers going out for at least a hundred miles or so. These days, he and his son, Isaac, take to the trails around the New Mexico region where the family has a rustic bit of property.

“Even if you know a lot about horses,” he says, “you’re not necessarily ready for something like a Long Ride. The old ways, like hobbling, are critical. We [Nelson and Preston] had to re-invent or re-discover some of the old ways. Most people saddle up, go riding, and come back to the barn.”

“I have found that feeding horses on a rigid schedule is not a good way to prepare a horse for a long ride,” he gives as an example on the LRG website (www.thelongridersguild.com), “when they might be turned out to graze at any time of the day or night or given feed at unexpected hours. Riding in the desert, you never know when you’re going to come across a beautiful patch of grass or when you’re going to pass by a ranch where you can buy oats. If you feed a horse on a rigid schedule he will be much more likely to colic when his feeding schedule is disrupted on the trail. What’s worse, a horse fed on a strict schedule becomes highly anxious on the trail when the feed times are delayed or changed or when there isn’t enough feed. So I try to alter feeding times and, once in a while, I actually skip a feeding time.”

“I do several other things with horses that I feel are essential to make a good long-rider horse, but which might not be usual for most horse lovers. In the wild, horses tend to drink twice a day, in the morning and at evening. It is good to train a horse to do without water, so they learn to drink well (but not over- or under-drink) when water is available. So at home, I let the horses only water twice a day and do not give them free, all-day-long access to water. On the trail, the horse does not get anxious or panicky at not having water all day, and when we do find water (I’ve done a lot of desert long-distance riding) the horse knows that he should drink well when he has the chance.”

Preston recognizes that the mainstream horse world now, is “oriented for people who ride around in the ring or arena.” It simply isn’t a world he finds appealing.

Preston recognizes that the mainstream horse world now, is “oriented for people who ride around in the ring or arena.” It simply isn’t a world he finds appealing.

“It’s all artificial,” he says. “All that stuff [typical rodeo and other arena sports] developed in the last 100 years or so. I don’t really think that’s authentic. It doesn’t comment on the true history of the horse. I stopped riding with those people because they were prissy and uptight. Even the men.”

“I did a bit of riding with Indians as well,” he continues. “Navajo mostly. They’re my kind of riders – riding bareback, or on crappy saddles, and on horses with conformational defects. But the Navajos have a sense of fun. We would ride like hell through the country. These horses and riders share a sense of wildness, and that’s my style of riding. All that stuff that I can’t stand, I think it crushes the spirit of the horse.”

Walter Neson

Photographer on the Trail

“Doug called up one day and said, ‘how’d you like to go on a trip with me?’” explains Walter Nelson about the beginning of their extraordinary Long Ride. “We just took off.”

Nelson possessed certain qualities that his neighbor in New Mexico, Douglas Preston, recognized made him a good candidate for going on the onerous excursion he proposed following in Coronado’s hoof prints. Nelson was a well-known photographer and artist possessing a certain openness of mind who had the guts to press onwards when others slunk back or laughed at the prospect of the journey, and growing up in Texas (and unlike Preston) he at least had a decent familiarity with horses. These proved essential aspects for the success of the journey that gained him a place among other tenacious adventurers who have earned membership in the Long Riders’ Guild.

Nelson possessed certain qualities that his neighbor in New Mexico, Douglas Preston, recognized made him a good candidate for going on the onerous excursion he proposed following in Coronado’s hoof prints. Nelson was a well-known photographer and artist possessing a certain openness of mind who had the guts to press onwards when others slunk back or laughed at the prospect of the journey, and growing up in Texas (and unlike Preston) he at least had a decent familiarity with horses. These proved essential aspects for the success of the journey that gained him a place among other tenacious adventurers who have earned membership in the Long Riders’ Guild.

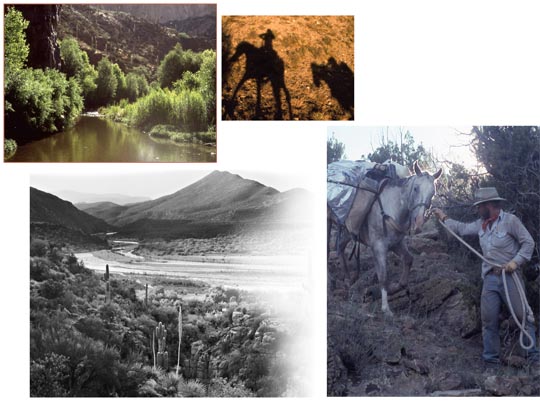

One of the most amazing aspects of this historical equestrian adventure through the unforgiving desert southwest was that Nelson documented it in photographs—not just any photographs snapped with a typical camera. Think more along the lines of Ansel Adams. Nelson brought along a pack horse for the task of hauling a Deardorf 8” x 10” camera, tripod, and the large format film along for the entire 1,000 mile adventure. With the age of digital technology upon us, this endeavor deep into the remote southwest may be the last to capture such images onto silver or platinum film plates.

“I had a sawbuck pack saddle,” he explains. “I had special saddle bags made out of high density foam padding and white tarpaulin that truckers use.”

Nelson customized the pack saddle to hold the delicate gear, and also covered the equipment when packed on the horse with a shiny metallic “space blanket.” This material cover reflected the heat of the 100+ degree days, and insulated the film and photographic equipment as much as possible. For the horse, it was surely a nice trade-off for packing the gear, as well.

“It [the space blanket] got shredded,” he says of one challenge that began early on. “From the start we went through curtains of green and brown. It was cat’s claw and mesquite.”

Nelson, now 65, bought the camera in New York City in 1981 when he worked there as a professional photographer.

“I just believe in doing things bigger,” he says, laughing about the burden of taking a hundred pounds of photographic gear into such a scorching and dusty place and over so many miles, then adds, “It was my primary camera for years and years. If you want to go into the landscape and photograph the landscape, the amount of information because of the size of the negative, 8” x 10,” is 50 times greater than a 35 mm camera. Your resolution doesn’t fall apart [in the printed image]…it holds together. A black and white silver print is so much more beautiful.”

Changing the extremely light sensitive film into different compartments of the pack was no small challenge on the trip. Nelson would wait until dark. Even then on the clear moonless desert nights, starlight was bright enough to affect the film. Preston had a tent onto which Nelson piled tarps, and then he would enter with the gear to quickly swap film around.

“Smithsonian underwrote the project,” Nelson explains of the Long Ride. They published numerous images he made on the journey with the Deardorf, which accompanied an article written by Preston. “It was a wonderful spread,” he says.

Recently, Nelson and Preston collaborated on another project, a book entitled, Ribbons of Time. The book is a portrait of a single, little known canyon in the Big Bend area of Texas which combines Nelson’s photography and Preston’s text.

For information on the book or other artistic and photographic works by Nelson visit: www.walterwnelson.com